Emil Nolde (nee Hansen) (1867-1956, 79)

The lash not the latte! Die Peitsche nicht die Latte!

The message not the aesthetic?

One off. A singular „primitive“ German Expressionist painter.

Not a „nice man“? No cosmopolitian multiculturalist: a pious, reactionary, pro-Nazi outsider.

But some striking modern paintings. If on his favoured old themes.

Nolde fits a 600 year tradition of serious, slightly mad, moralising, reactionary German art?

FEATURED

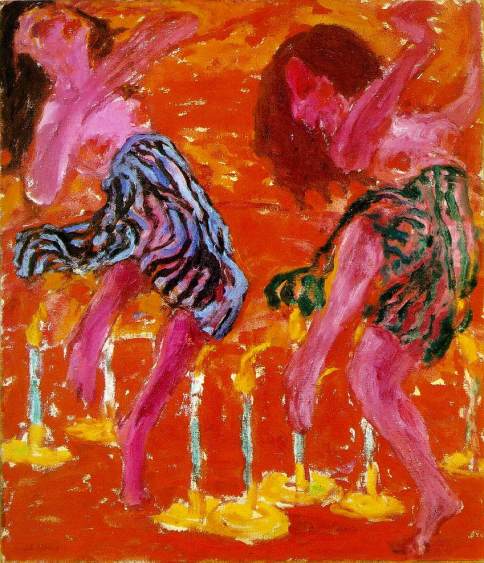

1920. Tänzerin und Harlekin (Dancer and Harlequin). 5 x 100 cm, oil on canvas (burlap).Nolde Foundation. COMMENT: at age 53, one of Nolde’s later (last?) quirky figure paintings, again invokes dancing.

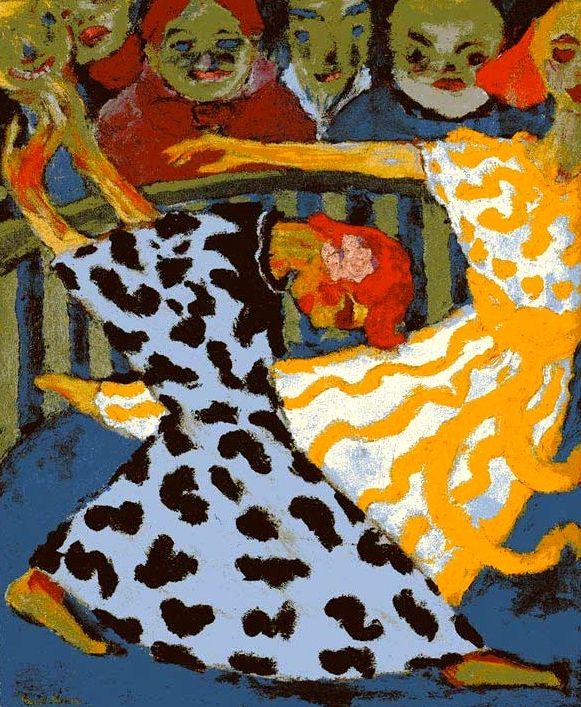

1909. Wildly Dancing Children (Enfants dansant sauvagement). 73 X 88, Kiel, Kunsthalle

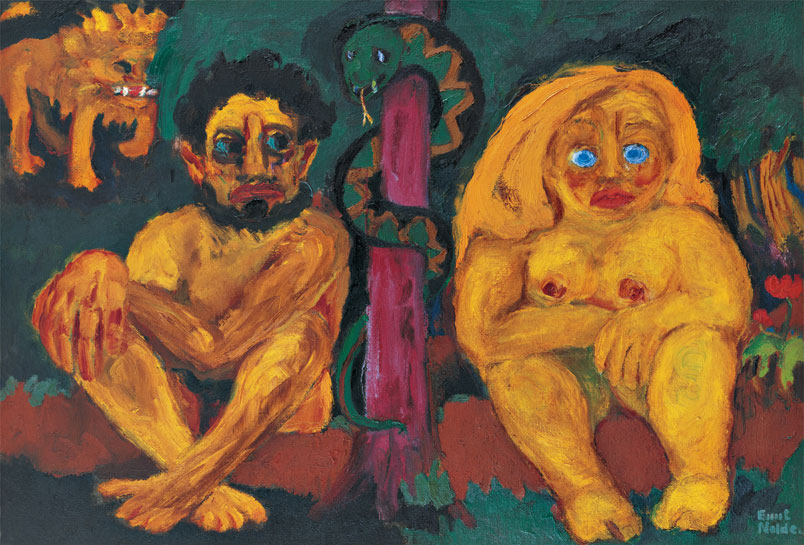

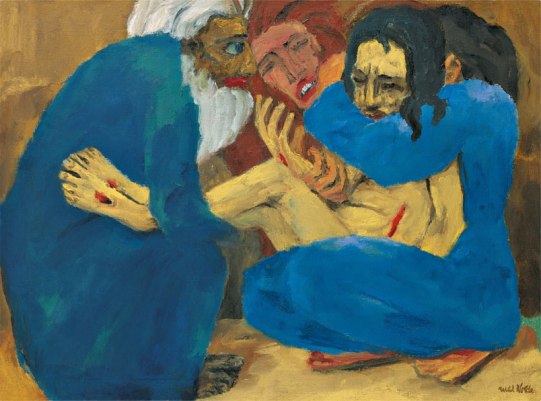

1921 Paradise Lost (Paradies verloren), oil on canvas, 86.5 x 100.5 cm, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

COMMENT: two signature Nolde works, an early Post-Impressionist cum Expressionist take on a timeless human theme, Dionysian revel, and a shell-shocked Aryan Eve in a later rowdy account of the foundation story for Christianity, the title making his point, a work which for some reason the Church was not keen to acquire.

Claude Monet (1840-1926). c1868. Coucher de soleil, pastel on paper, 21.8 x 35.8 cm. Est. GBP 200-300k.

COMMENT: Here is a Christies’ offering 28 February 2018, London, a simple small proto-Expressionist work by Monet, painted in the late 1860s, 6 years before Impressionism was officially launched, and about 60 years before Nolde was still painting much the same way by the Baltic.

1/ Summary

Emil Nolde was something else, different. For a brief spell before and around WW1 the Danish-German artist was a distinctly original Expressionist painter.

But as a leading Modernist he was also a strange if not unique mix of eye-catching art, a taciturn personality, little or no formal art training, and starkly un-modern“ old ideas, like old-time Christian religion and anti-Semitic pro-Nazi German nationalism.

But as such he arguably also fits well within a 600 year long tradition of slightly mad, moralising reactionary German art? The message not the aesthetic? „Die Botschaft nicht die Ästhetik?“

Though to be fair his copious colorful Baltic skyscapes and flowers showed he relaxed nearer the aesthetic pole.

His creative apogee was brief, only about a decade, c1909-19.

Appropriately, after finding his feet around 1905-08 (meeting the Die Brücke group, 1906-07, and Edvard Munch in 1906) Nolde in mid 1909 abruptly kick started his distinctive vigorous Expressionist style through religion. After recovering from illness that summer he embarked on a sequence of striking Expressionist religious paintings, like La Pentecôte (Pentecost), The Last Supper and Verspottung (Mocking of Christ by the Soldiers). In 1911/12 followed the huge 9 panel, The Life of Christ (centre panel 220.5 x 193.5 cm; the side panels each 100 x 86 cm), and 1915, the powerful compressed The Burial.

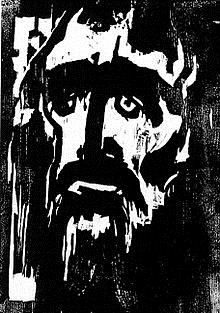

This theme then didn’t get much stranger than his wild 1912 tryptych on the unfamiliar St Mary of Egypt, an obscure and bizarre 7th C AD misogynistic story which also illustrates the Church’s problem with women. Also in 1912 came his iconic woodcut The Prophet of 1912. A decade later he unloaded with a shell-shocked Eve in Paradise Lost and a gory Martyrdom triptych.

From this religious passion he broadened his ambit to encompass what we might call primeval irrational urges, so striking too for elements of the primeval Dionysian madness within was a clutch of frantic dance themed images after 1910, and then many of his figure groups, like The Missionary (1912, painted before his New Guinea visit), Boy with a Big Bird (1912), Soldiers (1913), and Encounter on the beach (1920),

Then his creative flame waned after c1921? Beyond his mid 50s. He still painted a lot – many figures (portraits, small groups, some recalling post WW1 Francis Picabia?), many landscapes (sea and sky), and some flowers (lots of poppies and sunflowers) – mostly small and sketchy, in his trademark patchy colour-mad style. But mostly he was treading water, particulaly once proscribed by the Nazis.

„Primitive“ fits Emil Nolde, like his uncosmopolitan reactionary view of life: his strong attachment to his Christian faith, to his stark North Sea rural coastal home in far north Germany (a “regionalist“, Peter Selz, MOMA, 1963), and also to anti-Semitic German nationalism, later including a strong allegiance to the Nazis.

Which meant of course he was much closer to the then popular mindset than most of his avant-garde artist contemporaries.

And primitive fits his distinctive Expressionist painting style, developed especially when around age 42 he found his metier, Expressionist „modernist“ feet, just before WW1, c1909-14: coarse, ragged and colorful shapes, cropped, close up / in your face compositions, mask-like faces, figures with an element of the visceral, the grotesque and the crazy.

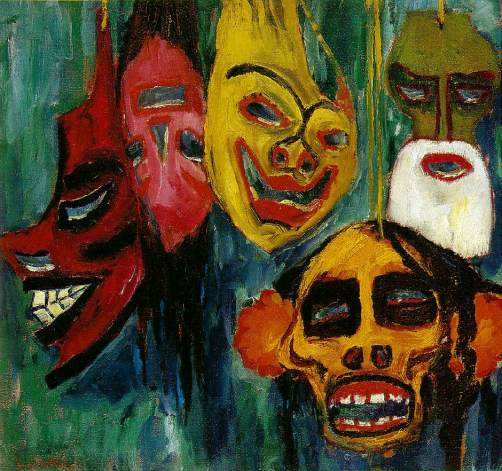

His 1913-14 ethnological visit to German New Guinea only whetted his existing appetite for the „primitive“, for he was already painting pictures of masks 2 years before, in 1911

He was an odd Modernist too in being older than his main contemporaries when he hit his straps around 1909 at age 42, except notably Kandinsky (who was a year older), also another Russian, fellow Expressionist Alexander Jawlensky (3 years older).

Like most people Nolde sought company and recognition, but his awkward personality constrained social engagement, and hence also his art training. For a time he was in the mix with other avant-garde painters (eg in particular when invited into Die Brucke, 1906–07), but temperamentally as well as politically he was out of step, the crusty old loner who quickly retreated from The Bridge, then from Berlin back to the rural Baltic.

His odd cocktail of circumstances became darkly comical after the Nazis took control in Germany early 1933 and especially when in 1937, unsurprisingly, the authorities deemed his colorful confronting modernism „degenerate“, showed him with other „degenerates“, and confiscated over 1000 works. The puzzled older artist (now near 70) pleaded for leniency, stressed his long running earnest and sincere support for Hitler and his Government!

2/ The lash not the latte? Die Peitsche nicht die Latte! The message not the aesthetic? Nolde fits in a 600 year long tradition of slightly mad, reactionary German art?

Here’s an original observation?

In seeking a wider perspective Nolde can be seen at least loosely as part of Germany (including the diverse collection of statelets it was pre the 19th C unification) having a long tradition of taking its art seriously, laboring the message not the aesthetic, and mostly favouring a reactionary nostalgic purpose, quasi-spiritual even, be it trumpeting Christianity or later calling on olden pagan Northern myths.

This is head down not feet up art.

So Germany was slow to accept the emerging artistic and cultural thrust of the Renaissance, swam against the tide, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries. Thus it contributed disproportionately to the so-called International Gothic art style, which tried to sustain the unnatural stylised Mediaeval painting, applied almost exclusively to asserting Christian iconography and per contra the radical shift to naturalism and realism which started in Italy late 13th / early 14th C with Pisano and Giotto.

This is evident for example in work of painters like the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece (active 1380-90, Prague), Master Francke (c1380-c1440), a German painter born in Lower Rhine, and the Master of the Karlsruhe Passion (active c1435-65), working in Strasbourg area.

Later, paradoxically, around 1500, as the High Renaissance was abroad in Italy and the Reformation was about to erupt across Europe, this anachronistic, reactionary neo-Mediaeval approach was then emphatically sustained by two stridently distinctive painters, Heironymous Bosch (1450-1516) in Flanders and Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470 – 1528) mostly in Mainz and Frankfurt. Both are probably far better known today than in their time, for their respective arresting contributions, their garish, visionary nightmarish proto-Surrealist imaginatons: Bosch in a unique one man admonitory c20 year moral crusade on behalf of the Roman Church, and Grunewald for one mighty religious work, his 11 panels for the Isenheim Altarpiece (c1506-16) focussing on the life of Christ. So both focussed exclusively on a didactic religious purpose, and both did so through graphic unnatural expression. Bosch’s younger contemporary, Hans Baldung Grien (c. 1484 – 1545), an apprentice to Durer, later based Strasbourg, also had a unique style and content, which also strayed into unnatural imagination and fantasy.

On the other hand the approach of the great virtuosic Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) – based mainly Nuremberg but broadened particularly by visits to Italy (1494-95 and 1505-07), also the Netherlands (1520-21) – was more equivocal, painted many religious images but avoided the ominous dark Boschian approach.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (no „h“) (c1525-1569) was a major Flemish artist in the mid 16th C, in the wake of the Reformation, now highly regarded and popular after about 3 centuries of neglect, and who died in his mid 40s, active for only c14 years. Bruegel painted religious works but mostly set in wintry Netherlands landscapes, early ones of which looked back Joachim Patinir (1483-1524, also Antwerp-based), except for 3 paintings c1562, where he did briefly follow Bosch’s visionary nightmarish model. Like Bosch a moralising theme threads his work, but in secular rural settings and he is now popular mostly for realistic depictions of peasant life.

Two other famous modern German artists, both slightly younger – Otto Dix (1891-1969) and George Grosz (1893-1959) – certainly fit the tradition of serious minded German art, Die Peitsche, in their fierce satirical assault on post WW1 Weimar Germany, through their graphic Expressionist leaning stylised realism (cf New Objectivity). But clearly they spoke from the other end of the political spectrum to Nolde, and were relentless, taking no time off for aesthetically therapeutic landscapes and still lives.

The slightly younger close contemporary Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956) was another German (American) painter who applied a modern artistic style to an anti-modern nostalgic purpose, leaving a raft of quasi-spiritual (Christian) aethereal luminous depictions of towns and churches, and seascapes and boats. But Feininger’ modern style was quite different toNolde, a much softer personal variant of Cubo-futurism, and incorporating a much louder aesthetic dimension than most of Nolde’s work.

However Nolde’s grotesque figures from his peak phase near and about WW1 do bear some resemblance to the distinctive elongated cartoon like figures in much of Feininger’s early painting (c 1910), which he carried over from his immediate prior career as a newspaper cartoonist.

On the other hand Feininger was far more conventional and social than Nolde, engaging far more closely with the art world, like his stint teaching with the Bauhaus.

Another distinctive Expressionist painter who Nolde met (in Munich?) and exhibited with, and whose work bears some comparison with Nolde, is the Russian expatriate (ie like Kandinsky) Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941).

Like Nolde he was also a late starter, but from very different circumstances. From a well off and well connected family he abandoned a military career for art. He was not overtly religious like Nolde though he was loosely “spiritual”and his many distinctive portraits / heads do draw on “traditional” roots, both Russian / Byzantine icons and “primitive” African sculpture.

Also, conspicuously, unlike Kandinsky (whose strong spiritualism, as for Mondrian, derived from the nonsensical strictures of Theosophy), neither Nolde nor Jawlensky crossed the line to pure abstraction.

Not surprisingly Nolde’s striking work has left its mark.

One can recognise American Modernist Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) in some of Nolde’s work (like Soldiers of 1913, which work Hartley may have seen in Germany near and at the start of WW1?

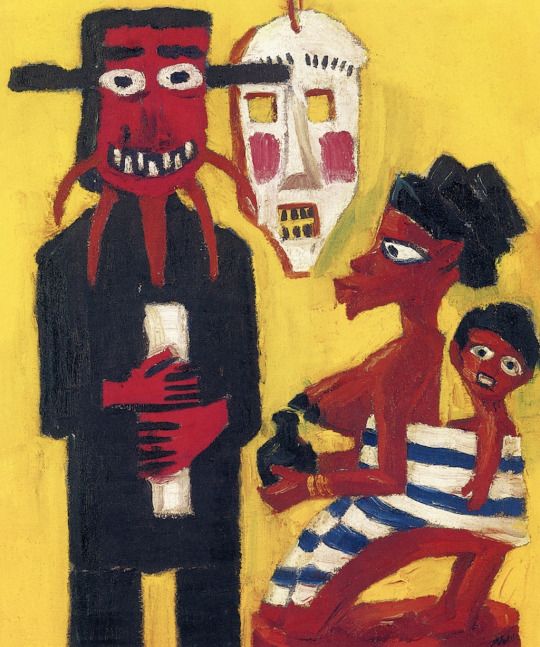

Also a couple of his works (like 1911, Figures exotiques 2 and Nature morte aux masques) seem to point directly to current market favourite Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88).

3/ The reactionary Modernist: a keen Nazi supporter and a Christian.

Nolde was an unusual Expressionist artist.

His painting style from c1909 was radical but unlike most of his cosmopolitan and politically progressive avant-garde colleagues he was staunchly reactionary. His strong traditional religious beliefs and conservative political views were directly out of step.

From a young age Nolde was a devout Christian, then from c1909, after illness, and over a period of about 15 years, he painted many confronting unconventional religious works, traditional Christian subjects but in a jarring modern style. And then he was apparently puzzled and hurt the Church did not commission any such works, or hang them!

More controversially, but far from unusual given his roots, Nolde became an early (from early 1920s?) and vociferous supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Party, and a racist denouncer of Jews (eg refer to work by Stefan Koldehoff and the catalogue for 2014 Frankfurt exhibition, Aya Soika and Bernhard Fulda): „For as long as I’ve worked as an artist I have publicly battled against the foreign infiltration of German art, against the dirty dealings on the art market and the disproportionately predominant Jewish influence everywhere in the arts..” (Emil Nolde notes, 6th December 1938).” “The sentences following this declaration consist of glowing endorsements of the Führer, Volk and Fatherland.” (Stefan Koldehoff).

Then self-interest reinforced his public support when in 1937, to his puzzled chagrin, the Nazis deemed his painting style „degenerate“, confiscated over 1000 of his works (1052?) and assigned 48 to the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition, Entartete Kunst. To no avail he pleaded for overturn of their rulings, eg in person to to Nazi gauleiter Baldur von Schirach in Vienna. Instead, on the contrary, in 1941 they ordered him to cease painting, which he quietly ignored, then painting 100s of watercolors which he secreted, calling them his “Unpainted Pictures“..

After WW2 however, like many Nazis, he quickly sought to evade responsibility, rewrite his history, cover his tracks, and (until recent times) with some official support.

4/ Driving his art content and style

Nolde was „spiritually“rooted to his locale in North Friesland in far north Germany, had a quasi-spiritual and nationalistic attachment, from 1902 taking his birthplace for his surname (Nolde is now in Denmark).

The main issues driving the content of his art were nature, religion, and the primal behaviour of people.

Nature he painted especially through his coastal home in north Germany, many landscapes and seascapes, through many floral still lives, also the Swiss mountains when he passed there as a young man.

His Christian religion was pivotal. These many important works started especially after illness in 1909, beginning with the Last Supper. Many followed, most like the Last Supper, then one crazy Noldesque one, Dance around the Golden Calf of 1910, culminating in his large neo-Mediaeval triptych of Life of Christ, 1911-12.

His woodcut of The Prophet (1912), dark and close, was an influential signature work, and later his Paradise (1921) was another arresting image, of a pivotal Biblical subject.

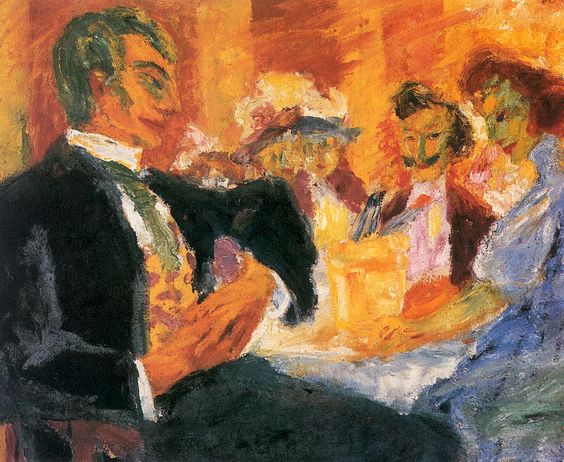

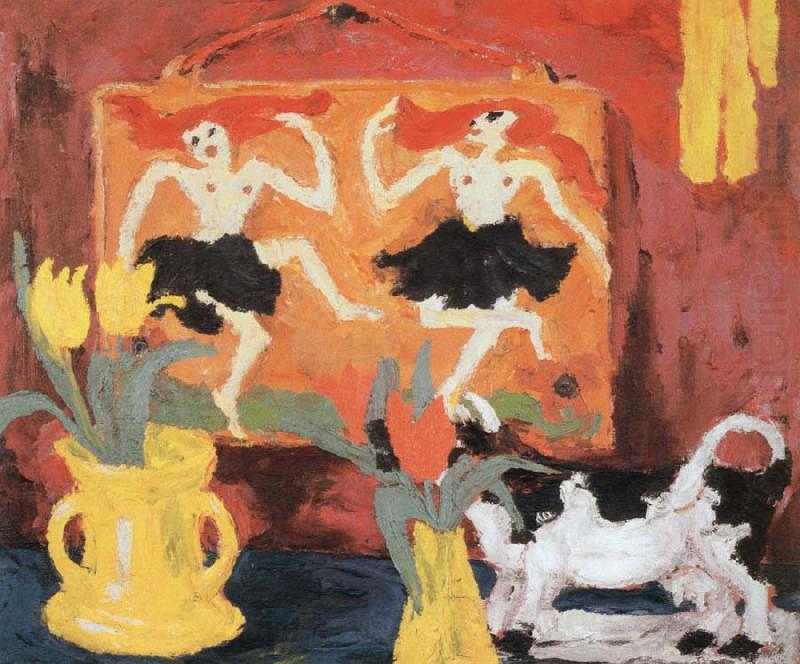

His attraction to what might be styled the primal passions of people is evident in his memorable depictions of the timeless theme of „dance“, but across various situations: like and children playing (1909, Wildly Dancing Children), and. like a night club (1914, Still life with dancers), and even, incongruously, religious settings! Like 1910‘s Dance Around the Golden Calf.

City life he saw in Berlin, then summer 1910 through the winter 1910-11 he explored Hamburg, the large northern port, painting many life scenes there, including cafes and night clubs, and including close up groups like the Slovenes and the Three Russians.

His art style, and longevity (thus avoiding two world wars and the great flu pandemic), allowed him to be prolific (eg Athenaeum list 1236 works), and across different media. Beyond oil paintings he left many watercolors, also many prints, etchings and woodcuts and lithographs.

The essence of his Expressionist style was bold bright colour in ragged untidy in your face close-ups. So his art style drew heavily on colour, lashings of, his „tempests of colour“ (Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976)), triggered especially it would seem by seeing works of Vincent van Gogh (1853-90) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) after around 1899.

„Every colour holds within it a soul, which makes me happy or repels me..”, he wrote.

In his many group figurative images (secular and religious) he favoured crowded close ups (like some famous past artists, cf the later Bosch), painting coarse ragged primtive like figures, drawing on caricature, the grotesque.

His painting method was spontaneous and quick, starting with „an idea“, then „I became the copyist of the idea“, working from his imagination, with little detailed preconception or preparation. Thus he was also prolific.

5/ One man’s journey.

5.1/ His own man, an outsider more than most.

Like many notable artists he followed his own muse, was his own man.

Socially he was awkward, shy and reclusive, wanted friends and acceptance, but struggled.

So in art he was largely self taught, partly because he had to work his way up from humble farming roots as a craftsman, but then especially because once he finally could afford some training, like in Paris , his personality meant he struggled, was not an easy student. He wrote “Paris has given me very little, and I had expected so much.” (Peter Selz, op.cit.).

For a time, from c1905, he met other artists, keen to exchange views, but again struggled. Much older than the others (eg 40 compared with mid to late 20s) Nolde in 1907 left the important pioneering Die Brücke Expressionist group after only about a year, not getting enough his own way.

His powerful unconventional modern religious paintings, unusual as avant-garde subjects, also aroused dissent.

After Die Brücke he joined the Berlin Secession, a group which rejected the conventional Association of Berlin Artists and favoured Post-Impressionism.

But 1910 he left that group after a “prolonged quarrel” following rejection of his 1910 Pentecost, and also works by other Exprssionists. He bitterly criticized Secession leader Max Liebermann (Jewish). Some of the rejected Expressionist painters (led by Tappert and Pechstein) in 1910 formed the breakaway Berlin Neue Secession, their first exhibition advertised as artists “rejected by the Berlin Secession 1910”. Nolde tried and failed in 1911 to take leadership of this group.

The art museum in Halle bought his Last Supper despite disagreement among the directors.

5.2/ Emergence as artist – largely self trained.

He was born Emil Hansen 1867 into an old devout Protestant farming family, one of 4 brothers, at Nolde in the western part of North Schleswig, then the Prussian (German) Duchy of Schleswig, becoming part of Denmark after WW1.

The German Expressionist painter and printmaker stayed close to his farming origins but not as a farmer, in 1884 (age 17) becoming an apprentice wood carver at a furniture factory (Sauermannsche Schnitzschule (Carving School)) at Flensburg, till 1888, thence 1889 (22) to work as a furniture carver at Karslruhe, taking art classes at night at Karlsruhe School of Applied Arts, then 1890-91 to Berlin as a furniture designer, but now drawing in museums. 1892-98 (age 25-31) he was a drawing instructor at Museum of Industry and Commerce in St Gallen in Switzerland and there finally encountered avant-garde art through Swiss painters, the neo-Romantic / Symbolist Arnold Bocklin (1827-1901) and Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918), impressed by their “allegorical, animistic” takes on nature, and by the dramatic natural scenery. Some financial success selling postcards of Symbolist like anthropomorphised mountains allowed him to seek further art training.

But 1899 he failed to enrol with Franz von Stuck in Munich, studied briefly instead at nearby Dachau with Adolf Hölzel (1853-1934), an interesting painter who at near age 60 helped pioneer abstraction, and who would have encouraged Nolde’s interest in colour.

He next spent 9 months in Paris to summer 1900, now studying at Académie Julian, where he met more new French art, but apparently departed very disappointed!

1900-02 he lived back near his roots, Copenhagen and nearby, 1903 settling on the island of Alsen, but also working in Berlin.

5.3/ Finds his feet

After a brief quiet start (cf Light be, 1901), and a visit to Italy 1904-05, by c1905 Nolde‘s distinctive colour hungry art style was becoming evident. In Nolde’s first colourful paintings c1905-07, mostly outdoors, like gardens and flowers, we see a clear line to especially van Gogh (eg Nolde‘s Harvest day, 1905, and Red flowers, 1906), and also Gauguin (eg Nolde‘s Market people, 1908).

But perhaps the immediate trigger of Expressionism in Germany, and presumably making a vital impact on Nolde was the Norwegian modern giant Edvard Munch (1863-1944), only 4 years older than Nolde but who made his mark much earlier, especially after being exposed in his mid-late 20s (c1889-1892) to the ongoing revolution in Paris, including Gauguin and van Gogh. Thus early as 1893 (age 30) Munch produced his first version his primally important The Scream. Later Nolde met Munch in Germany in 1906.

February 1906 Nolde was invited by the (17 years) younger Schmidt-Rottluff (“one of Die Brücke’s undertakings is to attract any ferment of revolution….. And so, dear Mr Nolde…. we hereby wish to pay tribute to you for your tempests of colour”) to join the Dresden-based German Expressionist group Die Brücke (founded 1905 by Fritz Bleyl (1880–1966), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976), Erich Heckel (1883-1970) etc). Schmidt-Rottluff, then introduced him to woodcut. Others included Max Pechstein (1881-1955).

Gustav Schiefler who he met in Berlin after 1902 was an important supportive patron, collected his work, wrote, and later produced a catalogue raisonné of his prints.

His painting style thereafter was variations on the colorfully „Expressive“, reinforced by his pre WW1 contact with other German Expressionists, through Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter.

Thus in 1912 Nolde showed with Kandinsky’s (1866-1944) and Franz Marc’s (1880-1916) important Munich-based group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), including Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Paul Klee (1879-1940), August Macke (1887-1914), Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956) and Albert Bloch (1881-1961).

The bold stylised art of “primitive” native people (especially sculpture, often accessed via museums) made a strong impressionon Nolde, as it had on many modern artists, and this was reinforced by being invited by the German Imperial Colonial Office to join a brief government ethnological excursion to German New Guinea, 1913-14, returning soon after WW1 broke out.

The other contemporary painter who resonates in some way with some of Nolde’s work was the Belgian James Ensor (1860-1949), 7 years older, and who Nolde visited in Ostend early 1911.

Ensor was similar to Nolde in a number of ways: he was also his own man, was also somewhat eccentric and reclusive; also painted Christian religious subjects (though less conventionally than Nolde, more as polemical expression of disllusion with the world); and finally, also he favoured elements of fantasy and the grotesque, especially for about a decade from the late 1880s (eg Masks Mocking Death, 1888), ie in his late 20s through 30s.

5.4/ And the rest

After WW1 when his home region became part of Denmark Nolde took Danish citizenship. Later, in 1927, he settled back near his roots by the North Sea coast, but at Seebüll, just inside the German border and today part of Neukirchen. There he built a house, now a museum.

Arguably the sting went out of Nolde’s work after the early 1920s, ie he in his mid 50s?

His output rate was far lower.

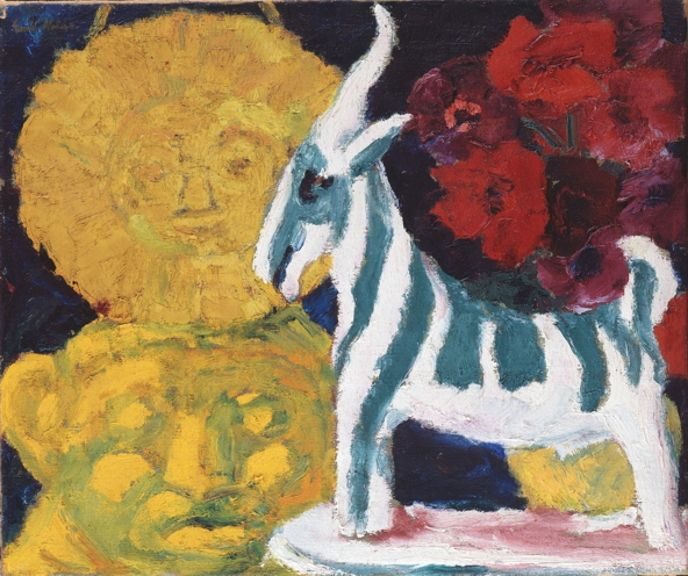

And in particular he retreated from his fierce slightly manic or frenzied Expressionist approach, from the aggressive style, and in the content, like no more of the many dance paintimgs, eg The Dancers (1920), and the quirky still lives, eg Striped goat and still life (1920).

There was still lots of colour but in a softer flat patchy style.

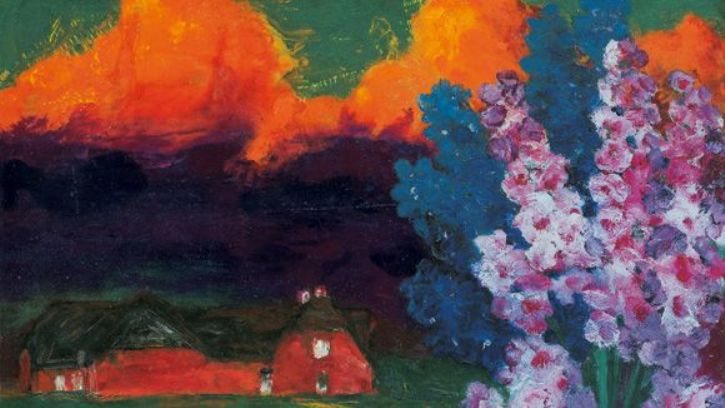

Lots of landscapes, lots of flowers, and some figures.

Then later, constrained by the Nazi rulings during WW2 he resorted to many small watercolours, his Unpainted paintings.

After his death in 1956 the Hamburg Kunstverein mounted a memorial exhibition at in 1957. Later he was exhibited in major exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (1963); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1995); Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (1995); Brücke-Museum, Berlin (1999); Grand Palais, Paris (2008); Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo (2012); and Frankfurt Städel Museum / Louisiana Museum of Modern Arts (2014).

SELECTED WORKS….

1907, Magic of light, (Lichtzauber), Oil on canvas, 70 x 88 cm. Nolde Stiftung Seebull

1910. Dance Around the Golden Calf, 88 x 105.5 cm

1911, Nature morte aux masques, 74 X 78, Kansas City, Nelson Gallery of Art, Atkins-Museum

1911 At the café (coffee house). Oil on canvas Museum Folkwang, Essen

1912. Boy with Grande Bird. Oil on canvas, 73 x 88 cm, SMK (Statens Museum for Kunst), Copenhagen

1912. The Prophet, 32.1 x 22.2 cm

1912 Legend: St. Mary of Egypt – Death in the Desert, Heilige Maria Aegyptiaca – Rechte Tafel: Der Tod in der Wüste). 1912, oil on canvas (Kunsthale Hamburg, Hamburg).

COMMENT: The story was written in the 7th C, of Saint Mary (Maria Aegyptiaca) who lived in 5th or 6th C, born Egypt, sold her body for living, “driven “by an insatiable and an irrepressible passion,””, who traveled to Jerusalem, “paid for her passage by offering sexual favors”, there saw the light, was “struck with remorse” and lived rest of her life across the Jordan as a hermit. The lion helped bury her.

1915. The Burial (Die Grablegung), oil on canvas, 87 x 117 cm, Stiftung Nolde, Seebüll, Nasjonalmuseet, National Museum of Art, , Architecture and Design, Norway

1912. Candle Dancers (Kerzentänzerinnen), Oil on canvas, 100.5 x 86.5 cm, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

1912. The Missionary, Private collection, 75 x 63 cm

1913. Soldiers, Oil on canvas, 86.5 x 106 cm, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

1914. Still life with dancers, oil on canvas 88 × 105.5 cm Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

1913 Clouds in Summer, Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 88.5 cm (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

- Shivering Russians,103.5 x 118.9 x 5.3 cm, SMK (Statens Museum for Kunst), Copenhagen

1917, Selbstbildnis, 1917, 83 x 65 cm, oil on wood. Nolde Foundation Seebüll , © Nolde Foundation Seebüll, 2013.

1918. Blue Sea (Blaues Meer). Oil on canvas, 56 x 70cm, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

1919 The enthusiast, Sprengel Museum Hanover 101.3 x 73.6cm

1920 Encounter on the beach, 86.5 x 100 cm, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

1920 Still Life with Striped Goat, 75 x 88cm, private

1920. Dancers

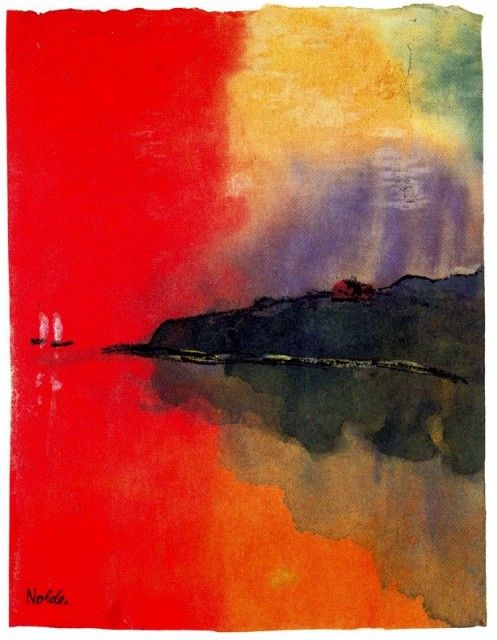

C 1930? Sea coast (Red Sky, Two White Sails), watercolor on Japan paper, 22.3 x 17.1cm. Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

1930. Schwü̈ler Abend (Muggy evening), Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Emil Nolde circa 1907? Age 40? And c 1945, age 78?